The identification of adults is straightforward due to a combination of the bright red bill, overall dark grey plumage, white-tipped black tail, and dark legs. Breeding-plumaged birds, with their white head, are particularly distinctive and unlikely to be confused with any other gull or seabird. Juvenile and immature birds, however, may cause some identification problems as their wholly dark brown or sooty plumage may recall several other species.

Immature Heermann’s Gulls is most likely to be confused with a dark-morph jaeger, particularly Pomarine Jaeger or Parasitic Jaeger. This is due both to a similarity in shape, size, and plumage as well as the tendency for Heermann’s Gulls to engage in piracy or kleptoparasitism in a manner that is more commonly associated with the jaegers. Adult jaegers will generally be easily distinguished by the presence of tail streamers, although these can be broken or missing and are not always reliable. In addition, all jaegers (adults and immatures) show a variable white flash in the primaries, visible both from above and (especially) from below. Heermann’s Gulls always show entirely dark wings with, at most, a narrow white trailing edge in older plumages. Despite the superficial similarities, immature Heermann’s Gulls are usually readily distinguishable from jaegers given reasonable views and shouldn’t cause more than momentary confusion in most circumstances.

| The vocalizations of this species are described as low, hollow, and trumpeting calls. These calls include a nasal yoww, a short yek, a high-pitched, whining whee-ee, and a repeated ye ye ye ye. Source: Sibley (2000); Islam (2002) |

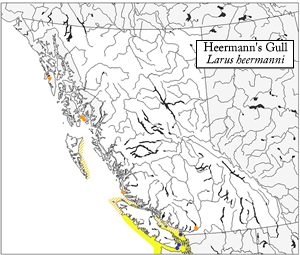

This species is a post-breeding visitor to B.C. and does not breed in the province.

|

This species forages solely in the marine environment, both in offshore and nearshore habitats, particularly where tidal rips, surge channels, or areas of upwelling bring abundant nutrients to the surface and concentrate prey. It commonly forages in small to medium-sized (occasionally large) flocks, usually associated with large numbers of California Gulls. It feeds primarily on small schooling fish (herring, sandlance, smelt), crustaceans (shrimp, amphipods, etc.), squid, and other marine invertebrates, but is an opportunistic feeder and will consume whatever is available. It often scavenges along the shoreline for carrion and other refuse but, unlike most other gull species, it does not frequent landfills. It picks food items from the surface of the water or from the ground in shoreline habitats, and will often dive shallowly from flight in order to reach prey that is below the surface of the water. It regularly engages in piracy, or ‘kleptoparasitism’, in which it chases and harasses other seabirds to encourage them to drop or disgorge whatever food they are carrying so that it can be stolen. The skuas and jaegers are experts at this type of behaviour, and some Heermann’s Gulls in B.C. have been observed to follow jaegers during these chases and pick up bits of disgorged food that are not taken by the jaeger. This species also congregates around foraging marine mammals (especially sea lions) in order to pick at the scraps of meat that are dispensed into the surrounding waters. It sometimes becomes very tame in areas that are frequented by people, and will sometimes even accept handouts of bread.

Source: Islam (2002); Campbell et al. (2007)

|

|